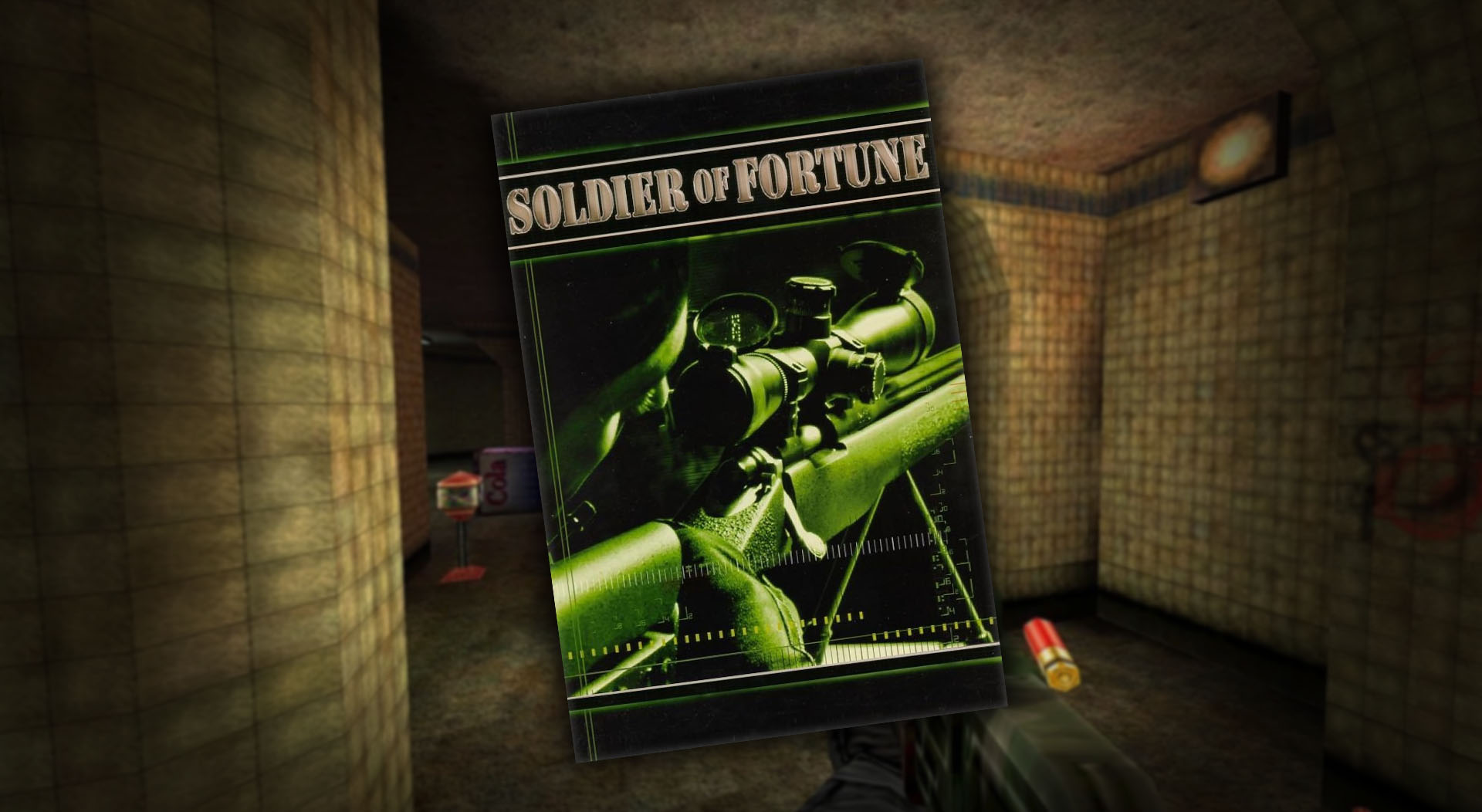

In the early 2000s, just as first-person shooters were shifting from sci-fi arenas to modern military theatres, Soldier of Fortune arrived with an unapologetic approach to violence and realism. Developed by Raven Software and published by Activision in 2000, the game stood apart from its contemporaries thanks to its graphic content, tactical gameplay, and moral ambiguity. For many Australian gamers, Soldier of Fortune became a cult classic, not just for the controversy, but for its unique place in the genre’s evolution.

A Shooter That Took Damage Modelling Seriously

While most FPS games of the era dealt in hit points and abstract damage numbers, Soldier of Fortune introduced something radically different: GHOUL, a proprietary engine that allowed players to target and damage specific body parts. Enemies could be disarmed, literally, or incapacitated with precise shots. Over 26 different hit zones per character brought an unsettling realism to the battlefield.

Raven Software’s lead designer detailed this system in an interview with GameSpot, stating that the GHOUL engine was intended to “give the player real-world feedback for their actions.” It wasn’t gore for gore’s sake, it made bullet placement strategic.

This locational damage system would go on to inspire future titles that built on the same visceral mechanics, such as Sniper Elite’s infamous x-ray kill cams and the limb-targeting in Fallout 3‘s V.A.T.S. system.

A Mercenary’s World: John Mullins and Military Grey Zones

Soldier of Fortune introduced players to John Mullins, a fictionalised version of a real-life mercenary who lent his name and expertise to the game’s development. The narrative followed Mullins through black ops missions in global hotspots, fighting terrorism outside official channels.

In contrast to the patriotic tone of Medal of Honor or the linear heroism in Call of Duty, Soldier of Fortune embraced moral ambiguity and gritty realism. This tone paved the way for later military games that strayed from clear-cut definitions of good and evil, most notably Spec Ops: The Line, which questioned the morality of modern warfare and player agency.

The Censorship Debate in Australia

In Australia, Soldier of Fortune sparked controversy before it even hit store shelves. The Office of Film and Literature Classification (OFLC) refused classification for the original title in 2000, effectively banning its sale due to its graphic violence and lack of an R18+ rating category for games at the time.

This ban highlighted the inadequacy of Australia’s classification system, which was only revised in 2013 to include an R18+ category for video games (Classification Board). While a censored version of Soldier of Fortune II: Double Helix was later released in Australia, it removed much of the visual brutality that had made the series distinctive.

Tactical Innovation Beyond Shock Value

Though often remembered for its gore, the Soldier of Fortune series introduced a surprising level of tactical depth. Double Helix (2002) featured mission-based gameplay, procedural levels through the “Random Missions Generator”, stealth mechanics, and AI behaviours that went beyond simple run-and-gun encounters.

This emphasis on realism predated similar shifts in tone seen in Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare (2007), which would go on to redefine military shooters with a cinematic but grounded approach. Double Helix also included realistic weapon behaviour and environmental interactions, such as reloading animations that varied depending on ammo count, something now standard in many tactical shooters.

Influenced by a Soldier: The Games That Followed

While not always directly credited, Soldier of Fortune left a noticeable mark on multiple franchises:

- Sniper Elite (2005–present): Rebellion’s sniper sim adopted locational damage and anatomical modelling similar to GHOUL, particularly its x-ray kill cam feature. Eurogamer notes the series’ commitment to body-specific shot reactions as part of its identity.

- Fallout 3 (2008): Bethesda’s V.A.T.S. system allows players to target limbs and body parts in turn-based shooting, conceptually similar to Soldier of Fortune’s manual aim focus.

- Dead Space (2008): Visceral Games’ horror shooter introduced the idea of “strategic dismemberment,” another evolution of body-specific gameplay tactics.

- Call of Duty: Modern Warfare series: The shift toward realism, brutal execution animations, and “clean house” missions, especially in the 2019 reboot, echo the tone of Double Helix. Polygon called the 2019 release “shockingly grounded” in a way rarely seen before in the series.

- Escape from Tarkov (2016–present): Battlestate Games’ hardcore shooter incorporates locational damage, bleeding, limping, and medical intervention, systems that mirror the direction Soldier of Fortune was heading more than 20 years ago.

The Fall from Grace: Soldier of Fortune: Payback

The third game in the series, Soldier of Fortune: Payback (2007), was developed without Raven Software and is widely seen as a misstep. Gone were the tactical elements and grounded tone, replaced by uninspired level design and arcade-style gunplay. Critics panned it for being generic and unambitious. IGN gave it a damning review, calling it “painfully mediocre.”

The failure of Payback effectively killed the series, but by then, its legacy had already been cemented in the DNA of many subsequent shooters.

A Legacy Worth Revisiting

Soldier of Fortune might not enjoy the mainstream recognition of Doom or Call of Duty, but its contribution to shooter realism, tactical dismemberment, and mature storytelling is undeniable. For Australian gamers, it was also a landmark case in the fight for fair classification, eventually contributing to the campaign that won adult ratings for games.

Today, the series lives on in memory and influence. Whether through the visceral headshots of Sniper Elite, the morally complex military fiction of Spec Ops: The Line, or the body-part tracking of Escape from Tarkov, echoes of John Mullins’ brutal world still ring out.